John Glenn

Submitted by admin on

| John Glenn | |

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Senator from Ohio |

|

| In office December 24, 1974 – January 3, 1999 |

|

| Preceded by | Howard Metzenbaum |

| Succeeded by | George Voinovich |

| Chairman of the Senate Committee on Governmental Affairs | |

| In office January 3, 1987 – January 3, 1995 |

|

| Preceded by | William V. Roth Jr. |

| Succeeded by | William V. Roth Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Herschel Glenn Jr. (1921-07-18)July 18, 1921 Cambridge, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | December 8, 2016(2016-12-08) (aged 95) Columbus, Ohio, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

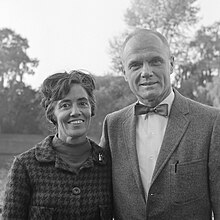

| Spouse(s) | Annie Glenn (m. 1943–2016) |

| Children | 2 |

| Residence | Columbus, Ohio[1] |

| Alma mater | Muskingum University, B.S. 1962 University of Maryland |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1941–1965 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | |

|

|

| NASA Astronaut | |

| Nationality | United States |

|

Other names

|

John Herschel Glenn, Jr. |

|

Other occupation

|

Test pilot |

|

Time in space

|

4h 55m 23s |

| Selection | 1959 NASA Group 1 |

| Missions | Mercury-Atlas 6 |

|

Mission insignia

|

|

| Retirement | January 16, 1964 |

| Awards | |

|

|

| NASA Payload Specialist | |

|

Time in space

|

9d 2h 39m |

| Missions | STS-95 |

|

Mission insignia

|

|

| Awards | |

John Herschel Glenn Jr. (July 18, 1921 – December 8, 2016) was an American aviator, engineer, astronaut, and United States Senator from Ohio. In 1962 he became the first American to orbit the Earth, circling three times. Before joining NASA, he was a distinguished fighter pilot in both World War II and Korea, with five Distinguished Flying Crosses and eighteen clusters.

He was one of the "Mercury Seven" group of military test pilots selected in 1959 by NASA to become America's first astronauts. On February 20, 1962, Glenn flew the Friendship 7 mission and became the first American to orbit the Earth and the fifth person in space. Glenn received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 1978, and was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1990. Glenn was the last surviving member of the Mercury Seven after the death of Scott Carpenter.

Glenn resigned from NASA in 1964 and announced plans to run for a U.S. Senate seat from Ohio. A member of the Democratic Party, he first won election to the Senate in 1974 where he served through January 3, 1999.

He retired from the Marine Corps in 1965, after twenty-three years in the military, with over fifteen medals and awards, including the NASA Distinguished Service Medal and the Congressional Space Medal of Honor. In 1998, while still a sitting senator, he became the oldest person to fly in space, and the only one to fly in both the Mercury and Space Shuttle programs as crew member of the Discovery space shuttle. He was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

Early life, education and military service

John Glenn was born on July 18, 1921, in Cambridge, Ohio, the son of John Herschel Glenn, Sr. (1895–1966) and Clara Teresa (née Sproat) Glenn (1897–1971).[2][3] He was raised in nearby New Concord.[4]

After graduating from New Concord High School in 1939, he studied Engineering at Muskingum College. He earned a private pilot license for credit in a physics course in 1941.[5] Glenn did not complete his senior year in residence or take a proficiency exam, both requirements of the school for the Bachelor of Science degree. However, the school granted Glenn his degree in 1962, after his Mercury space flight.[6]

World War II

When the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, Glenn quit college to enlist in the U.S. Army Air Corps. However, he was never called to duty, and in March 1942 enlisted as a United States Navy aviation cadet. He went to the University of Iowa for preflight training, then continued on to NAS Olathe, Kansas, for primary training. He made his first solo flight in a military aircraft there. During his advanced training at the NAS Corpus Christi, he was offered the chance to transfer to the U.S. Marine Corps and took it.[7]

Upon completing his training in 1943, Glenn was assigned to Marine Squadron VMJ-353, flying R4D transport planes. He transferred to VMF-155 as an F4U Corsair fighter pilot, and flew 59 combat missions in the South Pacific.[8] He saw combat over the Marshall Islands, where he attacked anti-aircraft batteries on Maloelap Atoll. In 1945, he was assigned to NAS Patuxent River, Maryland, and was promoted to captain shortly before the war's end.[4]:35

Glenn flew patrol missions in North China with the VMF-218 Marine Fighter Squadron, until it was transferred to Guam. In 1948 he became a flight instructor at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, followed by attending the Amphibious Warfare School.[9]:34

Korean War

During the Korean War, Glenn was assigned to VMF-311, flying the new F9F Panther jet interceptor. He flew his Panther in 63 combat missions, gaining the nickname "magnet ass" from his alleged ability to attract enemy flak.[10] On two occasions, he returned to his base with over 250 holes in his aircraft.[11] For a time, he flew with Marine reservist Ted Williams, a future Hall of Fame baseball player for the Boston Red Sox, as his wingman. He also flew with future Major General Ralph H. Spanjer.[12]

Glenn flew a second Korean combat tour in an interservice exchange program with the United States Air Force, 51st Fighter Wing. He logged 27 missions in the faster F-86F Sabre and shot down three MiG-15s near the Yalu River in the final days before the ceasefire.[10]

For his service in 149 combat missions in two wars, he received numerous honors, including the Distinguished Flying Cross (six occasions) and the Air Medal with eighteen award stars.[13]

Test pilot

Glenn returned to NAS Patuxent River, appointed to the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School (class 12), graduating in 1954.[14] He served as an armament officer, flying planes to high altitude and testing their cannons and machine guns.[15] He was assigned to the Fighter Design Branch of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics (now Bureau of Naval Weapons) as a test pilot on Navy and Marine Corps jet fighters in Washington, D.C., from November 1956 to April 1959, during which time he also attended the University of Maryland.[16]

Glenn had nearly 9,000 hours of flying time, with approximately 3,000 hours in jet aircraft.[16]

On July 16, 1957, Glenn completed the first supersonic transcontinental flight in a Vought F8U-3P Crusader.[17] The flight from NAS Los Alamitos, California, to Floyd Bennett Field, New York, took 3 hours, 23 minutes and 8.3 seconds. As he passed over his hometown, a child in the neighborhood reportedly ran to the Glenn house shouting "Johnny dropped a bomb! Johnny dropped a bomb! Johnny dropped a bomb!" as the sonic boom shook the town.[18] Project Bullet, the name of the mission, included both the first transcontinental flight to average supersonic speed (despite three in-flight refuelings during which speeds dropped below 300 mph), and the first continuous transcontinental panoramic photograph of the United States. For this mission Glenn received his fifth Distinguished Flying Cross.[19]

NASA career

While Glenn was on duty at Patuxent and Washington, Glenn began to read everything he could about space. His office was requested to furnish a test pilot to be sent to the Langley Air Force Base in Virginia to make some runs on a spaceflight simulator, which was a part of NASA research on reentry vehicle shapes. The officer would also be sent to the Naval Air Development Center in Johnsville, Pennsylvania. The test pilot would be subjected to high g-forces in a centrifuge to compare to the data collected in the simulator. Glenn requested this position and was granted it. He spent a few days at Langley and a week in Johnsville for the testing.[20]

Prior to Glenn's appointment as an astronaut in the Mercury program, he participated in the capsule design. NASA had requested that military service members participate in planning the mockup of the capsule. Since Glenn had participated in the research at Langley and Johnsville, combined he with his experience sitting on mock-up boards in the Navy and his knowledge of the capsule procedures, he was sent to the McDonnell plant in St. Louis and acted as a service adviser on the mock-up board.[20]

In 1958, the newly formed NASA began a recruiting program for astronauts,[a] and Glenn just barely met the requirements as he was close to the age cutoff of 40 and also lacked the required science-based degree at the time. He remained an officer in the United States Marine Corps after he was selected in 1959.[9]:43 After his selection, he was assigned to the NASA Space Task Group in 1959, which was located at Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.[21] The task force was moved to Houston in 1962 and became a part of the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center.[21] Glenn was a backup pilot to Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom, on the Freedom 7 and Liberty Bell 7 respectively.[21] Astronauts were given an additional role in the spaceflight program, and Glenn's was the cockpit layout and control functioning, not only for Mercury but also early designs for Apollo.[21]

Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, aboard Friendship 7 on February 20, 1962, on the Mercury-Atlas 6 mission, circling the globe three times during a flight lasting nearly five hours.[22] This made Glenn the third American in space and the fifth human being in space.[23][24][25][b] For Glenn the day became the "best day of his life," while it also renewed America's confidence.[31] His voyage took place while America and the Soviet Union were in the midst of the Cold War and competing in the "Space Race."[32]

During the flight, Glenn's heat shield had been thought to have come loose and likely to fail during re-entry, which would cause the entire space capsule to burn up. Flight controllers had Glenn modify his re-entry procedure by keeping his retrorocket pack on over the shield to help keep it in place. He made his splashdown safely, and afterwards it was determined that the indicator was faulty.[23] Glenn's flight and fiery splashdown was portrayed in the 1983 film The Right Stuff.[33]

Glenn is honored by President Kennedy at temporary Manned Spacecraft Center facilities at Cape Canaveral, Florida, three days after his flight

As the first American in orbit, Glenn became a national hero, met President Kennedy, and received a ticker-tape parade in New York City, reminiscent of that given for Charles Lindbergh and other great dignitaries.[23][34]

Glenn's fame and political attributes were noted by the Kennedys, and he became a personal friend of the Kennedy family. On February 23, 1962, President Kennedy escorted him in a parade to Hangar S at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, where he awarded Glenn with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal.[23]

In July 1962 Glenn testified before the House Space Committee in favor of excluding women from the NASA astronaut program. Although NASA had no official policy prohibiting women, in practice the requirement that astronauts had to be military test pilots excluded them entirely.[35][c]

Glenn resigned from NASA on January 16, 1964, and the next day announced his candidacy as a Democrat for the U.S. Senate from his home state of Ohio. On February 26, 1964, Glenn suffered a concussion from a slip and fall against a bathtub; this led him to withdraw from the race on March 30.[37][38] Glenn then went on convalescent leave from the Marine Corps until he could make a full recovery, necessary for his retirement from the Marines. He retired on January 1, 1965, as a Colonel and entered the business world as an executive for Royal Crown Cola.[23]

Political career

U.S. Senate

| This section is missing information about what Glenn did during his 24 years in the Senate. Please expand the section to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (December 2016) |

NASA psychologists had determined during Glenn's training that he was the astronaut best suited for public life.[39] Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy suggested to Glenn and his wife in December 1962 that he should run against incumbent United States Senator Stephen M. Young of Ohio in the 1964 Democratic primary election. In 1964 Glenn announced that he was resigning from the space program to run against Young, but withdrew when he hit his head on a bathtub. Glenn sustained a concussion and injured his inner ear, and recovery left him unable to campaign.[40] Glenn remained close to the Kennedy family and was with Robert Kennedy when he was assassinated in 1968. He served as a pallbearer at Kennedy's funeral.[4]:80

In 1970, Glenn was narrowly defeated in the Democratic primary for nomination for the Senate by fellow Democrat Howard Metzenbaum, by a 51% to 49% margin. Metzenbaum lost the general election race to Robert Taft, Jr. In 1974, Glenn rejected Ohio governor John J. Gilligan and the Ohio Democratic party's demand that he run for Lieutenant Governor. Instead, he challenged Metzenbaum again, whom Gilligan had appointed.[40]

In the primary race, Metzenbaum contrasted his strong business background with Glenn's military and astronaut credentials, saying his opponent had "never held a payroll". Glenn's reply came to be known as the "Gold Star Mothers" speech. He told Metzenbaum to go to a veterans' hospital and "look those men with mangled bodies in the eyes and tell them they didn't hold a job. You go with me to any Gold Star mother and you look her in the eye and tell her that her son did not hold a job." Many felt the "Gold Star Mothers" speech won the primary for Glenn.[41][42] Glenn won the primary by 54 to 46%. After defeating Metzenbaum, Glenn defeated Ralph Perk, the Republican Mayor of Cleveland, in the general election, beginning a Senate career that would continue until 1999. In 1980, Glenn won re-election to the seat, defeating Republican challenger Jim Betts, by over 40 percentage points.[43]

In 1986, Glenn defeated challenger U.S. Representative Tom Kindness. Metzenbaum would go on to seek a rematch against Taft in 1976, winning a close race on Jimmy Carter's coattails.[44]

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Glenn and Metzenbaum had strained relations. There was a thaw in 1983, when Metzenbaum endorsed Glenn for president, and again in 1988, when Metzenbaum was opposed for re-election by Cleveland mayor George Voinovich. Voinovich accused Metzenbaum of being soft on child pornography. Voinovich's charges were criticized by many, including Glenn, who now came to Metzenbaum's aid, recording a statement for television rebutting Voinovich's charges. Metzenbaum won the election by 57% to 41%.[44] In 1997, Glenn announced that he would retire from the Senate at the end of his then-current term.[45]

Savings and loan scandal

Glenn was one of the five U.S. senators caught up in the Lincoln Savings and Keating Five Scandal after accepting a $200,000 contribution from Charles Keating. Glenn and Republican senator John McCain were the only senators exonerated. The Senate Commission found that Glenn had exercised "poor judgment". The association of his name with the scandal gave Republicans hope that he would be vulnerable in the 1992 campaign. Instead, Glenn defeated Lieutenant Governor Mike DeWine to keep his seat.[46]

Presidential politics

In 1976, Glenn was a candidate for the Democratic vice presidential nomination. However, Glenn's keynote address at the Democratic National Convention failed to impress the delegates and the nomination went to veteran politician Walter Mondale.[47] Glenn also ran for the 1984 Democratic presidential nomination.[48]

Glenn and his staff worried about the 1983 release of The Right Stuff, a film about the original seven Mercury astronauts based on the best-selling Tom Wolfe book of the same name. The book had depicted Glenn as a "zealous moralizer", and he did not attend the film's Washington premiere on October 16, 1983. Reviewers saw Ed Harris' portrayal of Glenn as heroic, however, and his staff immediately began to emphasize the film to the press. Aide Greg Schneiders suggested an unusual strategy, similar to Glenn's personal campaign and voting style, in which he would avoid appealing to narrow special interest groups and instead seek to win support from ordinary Democratic primary voters, the "constituency of the whole".[40] Mondale defeated Glenn for the nomination however, and he was left with $3 million in campaign debt for over 20 years before he was granted a reprieve by the Federal Election Commission.[49][50] He was a potential vice presidential running mate in 1984, 1988, and 1992.[51]

Issues

During Glenn's time in the Senate, he was chief author of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978,[52] served as chairman of the Committee on Governmental Affairs from 1987 until 1995, sat on the Foreign Relations and Armed Services committees and the Special Committee on Aging.[53]

Once Republicans regained control of the Senate, Glenn served as the ranking minority member on a special Senate investigative committee chaired by Tennessee senator Fred Dalton Thompson that looked into illegal foreign donations by China to U.S. political campaigns for the 1996 election.[54] There was considerable acrimony between the two men during the life of this committee.[55]

Return to space

Glenn returned to space on the Space Shuttle on October 29, 1998, as a Payload Specialist on Discovery's STS-95 mission, becoming, at age 77, the oldest person to go into space. According to The New York Times, Glenn "won his seat on the Shuttle flight by lobbying NASA for two years to fly as a human guinea pig for geriatric studies", which were named as the main reasons for his participation in the mission.[56] Shortly before the flight, researchers learned that Glenn had to be disqualified from one of the flight's two main priority human experiments (about the effects of melatonin) because he did not meet one of the study's medical conditions; he still participated in two other experiments about sleep monitoring and protein use.[56][57]

Glenn states in his memoir that he had no idea NASA was willing to send him back into space when NASA announced the decision.[58] His participation in the nine-day mission was criticized by some in the space community as a political favor granted to Glenn by President Clinton, with John Pike, director of the Space Policy Project for the Federation of American Scientists noting "If he was a normal person, he would acknowledge he's a great American hero and that he should get to fly on the shuttle for free...He's too modest for that, and so he's got to have this medical research reason. It's got nothing to do with medicine."[23][59]

In a 2012 interview, Glenn said that the purpose of his flight was "to make measurements and do research on me at the age of 77 [...] comparing the results on me in space with the younger [astronauts] and maybe get [insights] on the immune system or protein turnover or vestibular functions and other things — heart changes.[57] He regretted that NASA did not follow up on this research about aging by sending more people from this age range into space.[57]

Upon the safe return of the STS-95 crew, Glenn (and his crewmates) received another ticker-tape parade, making him the tenth, and latest, person to have received multiple ticker-tape parades in a lifetime (as opposed to that of a sports team).[60] Just prior to the flight, on October 15, 1998, and for several months after, the main causeway to the Johnson Space Center, NASA Road 1, was temporarily renamed "John Glenn Parkway".[61]

In 2001, Glenn vehemently opposed the sending of Dennis Tito, the world's first space tourist, to the International Space Station on the grounds that Tito's trip served no scientific purpose.[62]

Public affairs institute

Glenn helped found the John Glenn Institute for Public Service and Public Policy at The Ohio State University in 1998 to encourage public service. On July 22, 2006, the institute merged with OSU's School of Public Policy and Management to become the John Glenn School of Public Affairs, and Glenn held an adjunct professorship at the Glenn School.[63] In February 2015, it was announced that the School would become the John Glenn College of Public Affairs beginning in April 2015.[64]

Personal life

On April 6, 1943, Glenn married his high school sweetheart, Anna Margaret Castor (b. 1920). Both Glenn and his wife attended Muskingum College in New Concord, Ohio, where he was a member of the Stag Club Fraternity.[65] Together, they had two children, John David and Carolyn Ann, and two grandchildren.[4]:31 They remained married until his death. His boyhood home in New Concord has been restored and made into an historic house museum and education center.[66]

A Freemason, Glenn was a member of Concord Lodge # 688 New Concord, Ohio, and DeMolay International, the Masonic youth organization, and was an ordained elder in the Presbyterian Church.[67]

He set an example of someone whose faith began before he became an astronaut, and whose faith was reinforced after traveling in space.

"To look out at this kind of creation and not believe in God is to me impossible," said Glenn, after his second and final space voyage.[68] He stated that he saw no contradiction between believing in God and the knowledge that evolution is "a fact", and that he believed evolution should be taught in schools.[69] He explained:

I don't see that I'm any less religious that I can appreciate the fact that science just records that we change with evolution and time, and that's a fact. It doesn't mean it's less wondrous and it doesn't mean that there can't be some power greater than any of us that has been behind and is behind whatever is going on.[70]

Glenn was one of the original owners of a Holiday Inn franchise near Orlando, Florida, that is today known as the Seralago Hotel & Suites Main Gate East.[71][72] His business partner was Henri Landwirth, a Holocaust survivor, who became Glenn's "best friend."[73] Glenn recalls learning about Landwirth's background:

Henri doesn't talk about it much. It was years before he spoke about it with me and then only because of an accident. We were down in Florida during the space program. Everyone was wearing short-sleeved Ban-Lon shirts—everyone but Henri. Then one day I saw Henri at the pool and noticed the number on his arm. I told Henri that if it were me I'd wear that number like a medal with a spotlight on it.[73]

Public appearances and ceremonies

Glenn was an honorary member of the International Academy of Astronautics; a member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, Marine Corps Aviation Association, Order of Daedalians, National Space Club Board of Trustees, National Space Society Board of Governors, International Association of Holiday Inns, Ohio Democratic Party, State Democratic Executive Committee, Franklin County (Ohio) Democratic Party, and 10th District (Ohio) Democratic Action Club.[5]

In 2001, Glenn appeared as a guest star on the American television sitcom Frasier, as himself.[74]

On September 5, 2009, John and Annie Glenn dotted the "i" during The Ohio State University's Script Ohio marching band performance, at the Ohio State–Navy football game halftime show. Other non-band members to have received this honor include Bob Hope, Woody Hayes, Jack Nicklaus and Earle Bruce.[75]

On February 20, 2012, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Friendship 7 flight, Glenn was surprised with the opportunity to speak with the orbiting crew of the International Space Station while Glenn was on-stage with NASA Administrator Charlie Bolden at The Ohio State University, where the public affairs school is named for him.[76]

On April 19, 2012, Glenn participated in the ceremonial transfer of the retired Space Shuttle Discovery from NASA to the Smithsonian Institution for permanent display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Speaking at the event, Glenn criticized the "unfortunate" decision to end the Space Shuttle program, expressing his opinion that grounding the shuttles delayed research.[77]

In June 2016 the Columbus, Ohio airport known for many years as Port Columbus was officially renamed the John Glenn Columbus International Airport. Just before his 95th birthday, Glenn and his wife Annie attended the ceremony, and he spoke about how visiting that airport as a child inspired his interest in flying.[78]

Illness and death

In June 2014, Glenn underwent a successful heart valve replacement surgery at the Cleveland Clinic.[79]

At the beginning of December 2016, Glenn was hospitalized at the James Cancer Hospital of OSU Wexner Medical Center in Columbus for a variety of health issues.[80][81][82] A family source said that Glenn had been in declining health, and that his condition was grave. His wife, Annie, and their children and grandchildren had joined him at the hospital.[83]

Glenn died December 8, 2016, at the OSU Wexner Medical Center.[84][85] No cause of death has yet been disclosed. Glenn will be interred at Arlington National Cemetery after lying in state at the Ohio Statehouse and a memorial service at Mershon Auditorium at The Ohio State University.[84]

Tributes

Among those honoring Glenn were President Barack Obama, who said that Glenn, "the first American to orbit the Earth, reminded us that with courage and a spirit of discovery there's no limit to the heights we can reach together."[86] Tributes were also given by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton,[87] and President-elect Donald Trump.[88]

Image gallery

-

Medical debriefing of Major John H. Glenn, Jr., USMC after orbital flight of Friendship 7 on February 20, 1962 aboard the aircraft carrier USS Randolph (CVS-15). The debriefing team for Lt. Colonel Glenn (center) was led by Commander Seldon C. "Smokey" Dunn, MC, USN (FS) (RAM-qualified) (far right w/EKG in hands).

-

Plaque near Mercury launch pad

Awards and honors

|

|||

- Congressional Gold Medal[90]

- The Woodrow Wilson Award[91]

- National Geographic Society's Hubbard Medal, 1962[92]

- John J. Montgomery Award, 1963[93]

- General Thomas D. White National Defense Award.[94]

Quincy Jones presents platinum copies of "Fly Me to the Moon" (from It Might as Well Be Swing) to Senator John Glenn (left) and Apollo 11 Commander Neil Armstrong (right)

The NASA John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field in Cleveland, Ohio, is named after him. Also, Senator John Glenn Highway runs along a stretch of I-480 in Ohio across from the NASA Glenn Research Center. Colonel Glenn Highway, which runs by Wright-Patterson Air Force Base and Wright State University near Dayton, Ohio, John Glenn High School in his hometown of New Concord, Ohio, and Col. John Glenn Elementary in Seven Hills, Ohio, are named for him as well. High Schools in Westland and Bay City, Michigan; Walkerton, Indiana; San Angelo, Texas; Elwood, Long Island, New York; and Norwalk, California were also named after him.

The fireboat John H. Glenn Jr. was named for him. This fireboat is operated by the DCFD and protects the sections of the Potomac River and the Anacostia River that run through Washington, D.C.

The USNS John Glenn (T-MLP-2), a mobile landing platform that was delivered to the U.S. Navy on March 12, 2014, is named for him. It was christened February 1, 2014, in San Diego at General Dynamics’ National Steel and Shipbuilding Company.[95]

In 1961, Glenn received an Honorary LL.D from Muskingum University, the college he had attended before joining the military in World War II.[6] He received Honorary Doctorates from Nihon University in Tokyo, Japan, Wagner College in Staten Island, New York, and New Hampshire College in Manchester, New Hampshire.

Glenn was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1976.[96] Glenn was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 1977.[25]

In 1990, Glenn was inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame.[97]

In 2000, Glenn received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[98]

In 2004, Glenn was awarded the Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars of the Smithsonian Institution.[99]

In 2009, Glenn received an Honorary LL.D from Williams College,[100] and in 2010, he received an Honorary Doctorate of Public Service from Ohio Northern University.[101]

In 2013, Flying magazine ranked Glenn No. 26 on their "51 Heroes of Aviation" list.[102]

On September 12, 2016, Blue Origin announced a new rocket named after Glenn, the New Glenn.[103]

See also

- List of spaceflight records

- The John Glenn Story, a 1962 documentary film

- Project Mercury Commemorative stamp

Notes

- Jump up ^ Requirements were that each had to be a military test pilot between the ages of 25 and 40 with sufficient flight hours, no more than 5'11" in height, and possess a degree in a scientific field. 508 pilots were subjected to rigorous mental and physical tests, and finally the selection was narrowed down to seven astronauts (Glenn, Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, Scott Carpenter, Wally Schirra, Gordon Cooper, and Deke Slayton), who were introduced to the public at a NASA press conference in April 1959.

- Jump up ^ Perth, Western Australia, became known worldwide as the "City of Light"[26] when residents turned on their house, car and streetlights as Glenn passed overhead.[27][28] The city repeated the act when Glenn rode the Space Shuttle in 1998.[29][30]

- Jump up ^ The impact of the testimony of so prestigious a hero is debatable, but no female astronaut flew on a NASA mission until Sally Ride in 1983 (in the meantime, the Soviets had flown two women on space missions), and none piloted a mission until Eileen Collins in 1995, more than 30 years after the hearings. In the late 1970s, Glenn was reported to have supported Shuttle Mission Specialist Astronaut Judith Resnik in her career.[36]

References

- Jump up ^ Ohio (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Publishing Office. 1997. p. 104. ISBN 978-9997687630.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn Archives, Audiovisuals Subgroup, Series 3: Certificates". Library.osu.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-12-21. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Jump up ^ "Ancestry of John Glenn". Famous Kin. United States: GenealogyMagazine. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kupperberg, Paul (November 1, 2003). John Glenn: The First American in Orbit and His Return to Space. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 15, 35. ISBN 978-0-8239-4460-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "40th Anniversary of Mercury 7: John Herschel Glenn, Jr.". History.nasa.gov. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (4 October 1983), "College says Glenn degree was deserved", The Day (New London, CT).

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn: Biographical Sketch". Ohio Statue University. 2009. Archived from the original on October 17, 2009.

- Jump up ^ Shettle USMC Air Station of WWII, p. 167

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tilton, Rafael. John Glenn, Lucent Books (2000)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chaikin, Andrew. John Glenn: America's Astronaut, Smithsonian Institution (2014) ebook

- Jump up ^ Mersky USMC Aviation, p. 183

- Jump up ^ "Ralph H. Spanjer, 78". Chicago Tribune. Chicago: Tronc Inc. February 12, 1999. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ John Glenn, astronaut and senator, dead at age 95", USA Today, December 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ Vogel, Steve (1998-06-07). "PAX RIVER YIELDS A CONSTELLATION OF ASTRONAUT CANDIDATES". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Chaikin, Andrew (April 15, 2014). John Glenn: America's Astronaut. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9781588344861.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Astronaut Bio: John Glenn, Jr. 1/99". www.jsc.nasa.gov. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Silent Seven: John Glenn, last Mercury astronaut, dies at 95 – SpaceFlight Insider". www.spaceflightinsider.com. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Green, Robert (January 1, 2009). John Glenn. Chicago, Illinois: Ferguson Publishing Company. ISBN 9781438111957.

- Jump up ^ Glenn, John; Taylor, Nick (November 2, 1998). John Glenn: A Memoir. Bantam. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-553-11074-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gray, Tara. "John H. Glenn, Jr.". NASA History Program Office. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Biographical Data". NASA JSC. January 1999. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Glenn Orbits the Earth". NASA. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Staff (October 8, 1998). "John Glenn Stirs Controversy". CBSNews.com. CBS. Retrieved December 7, 2016. There are people at NASA who have said this is a multi-million dollar joy ride for someone who supports President Clinton, and he's getting a payback.

- Jump up ^ NBC News broadcast of John Glenn's 1962 space flight

- ^ Jump up to: a b "International Space Hall of Fame :: New Mexico Museum of Space History :: Inductee Profile". Nmspacemuseum.org. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ City of light - 50 years in Space | Western Australian Museum

- Jump up ^ (1970) Perth – a city of light Perth, W.A. Brian Williams Productions for the Government of WA, 1970 (Video recording) The social and recreational life of Perth. Begins with a 'mock-up' of the lights of Perth as seen by astronaut John Glenn in February 1962

- Jump up ^ Gregory, Jenny. "Biography – Sir Henry Rudolph (Harry) Howard – Australian Dictionary of Biography". Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Jump up ^ Australian Broadcasting Corporation (February 15, 2008). "Moment in Time – Episode 1". Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Jump up ^ Moore, Charles (November 5, 1998). "Grandfather Glenn's blast from the past". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn Dead at 95 | John Glenn Celebrates Orbiting the Earth", ABC News, Feb. 20, 2012

- Jump up ^ Koren, Marina. "Remembering John Glenn", The Atlantic, Dec. 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ John Glenn's orbit in The Right Stuff, enacted by Ed Harris

- Jump up ^ Photo of Glenn's ticker-tape parade down Broadway in New York, March 1, 1962

- Jump up ^ Nolan, Stephanie (October 12, 2002). "One giant leap - backward: Part 2". The Globe and Mail. Toronto: The Woodbridge Company. Archived from the original on September 13, 2004. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Kevles, Betty Ann Holtzmann (2003). Almost Heaven: the Story of Women in Space. New York City: Basic Books. p. 98. ISBN 0-738202096.

- Jump up ^ Pett, Saul (May 10, 1964). "John Glenn's Irony: He Fights for Balance". The Tennessean. Nashville, Tennessee: Gannett Company. p. 2.

- Jump up ^ Mattson, Dr. Richard H (March 31, 1964). "Doctors Urge He Quit Race". New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. p. 19.

- Jump up ^ Catchpole 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Raines, Howell (November 13, 1983). "John Glenn: The Hero as Candidate". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. p. 40. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- Jump up ^ Koli, Monika (August 9, 2016). 20 Greatest Astronauts of the World. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 18.

- Jump up ^ Kennedy, Eugene (October 11, 1981). "JOHN GLENN'S PRESIDENTIAL COUNTDOWN". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Knight, Jonathan (2003). Kardiac Kids: The Story of the 1980 Cleveland Brown. Kent State University. Kent State University. p. 114. ASIN B005EP2VRQ. ISBN 0-873387619.

- ^ Jump up to: a b OH US Senate campaign

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn". Muskingum University. Archived from the original on July 15, 2003. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Jump up ^ Clifford Krauss Krauss, Clifford (October 15, 1992). "In Big Re-election Fight, Glenn Tests Hero Image". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn's Presidential Countdown". The New York Times. Oct 11, 1981. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Raines, Howell (November 13, 1983). "John Glenn: The Hero as Candidate". The New York Times. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Luce, Edward (May 9, 2008). "Well of donors dries up for Clinton". Ft.co. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Jump up ^ "For Clinton, Millions in Debt and Few Options". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. June 10, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn, First American To Orbit The Earth, Dies At 95", NPR], December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Nayan, Rajiv (September 13, 2013). The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and India. Routledge. ISBN 9781317986102.

- Jump up ^ "Former Senator and Astronaut John Glenn Dies at 95". Roll Call. December 8, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Majority Media – Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs Committee". hsgac.senate.gov. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Fred Thompson's Big Flop". Portfolio.com. October 15, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Altman, Lawrence K. (October 21, 1998). "Glenn Unable to Perform Experiment Planned for Space Flight". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Riley, Brian (2012). "Interview with John Glenn". Davis, California: BrianRiley.us. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Glenn, John; Taylor, Nick (November 2, 1998). John Glenn: A Memoir. Bantam. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-553-11074-6.

- Jump up ^ McCutcheon, Chuck (April 25, 1998). "Critics: Glenn Flight A Boost For NASA, Not Science". CNN. United States: Congressional Quarterly. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- Jump up ^ List of ticker-tape parades in New York City

- Jump up ^ Weinberg, Eliot (October 30, 1998). "Pilgrims come from near, far for Discovery's launch". The Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach, Florida, USA. p. 10. Retrieved December 8, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn: Space tourist cheapening Alpha". CNN. May 3, 2001. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- Jump up ^ "JOHN H. GLENN Jr.". Ohio State University. Columbus, Ohioarchiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20141207161218/http://glennschool.osu.edu/about/john_glenn.htmlDate=December 7, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2016. [dead link]

- Jump up ^ "Welcome to John Glenn College of Public Affairs | The Columbus Dispatch". Dispatch.com. February 4, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ Muskingum College (October 16, 1998). "Muskingum Grad to Conduct Solar Experiments Aboard Oct. 29 Shuttle Flight with Muskie John Glenn on Board". PR Newswire. New York City: Cision Inc. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ "The John & Annie Glenn — Historic Site". Johnglennhome.org. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ Kupperberg, Paul (2003). John Glenn profile. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 96. ISBN 9780823944606. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- Jump up ^ "In space, John Glenn saw the face of God: ‘It just strengthens my faith’", Washington Post, Dec. 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn Says Evolution Should Be Taught In Schools". The Huffington Post. United States: AOL. May 20, 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-03-10. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- Jump up ^ "Astronaut, senator and Presbyterian John Glenn saw no conflict between beliefs in God and science", Religion News Service, Dec. 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ "The History of our Kissimmee Family Hotel". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Landwirth, Henri (1996). Gift of Life. United States: Private Printing Publishing. ASIN B005V5JKFK.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kramer, Michael. "John Glenn: The Right Stuff", New York Magazine, January 31, 1983, p. 24

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn appears on Emmy-award winning 'Frasier'". Ohio State University. Columbus, Ohio. March 5, 2001. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Traditions". Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ Franko, Kantele (February 20, 2012). "Armstrong honors Glenn 50 years after his orbit – NASA also surprised Glenn with space station chat". MSNBC. United States: NBCUniversal (Comcast). Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- Jump up ^ Zongker, Brett (April 20, 2012). "Shuttle Discovery lands at Smithsonian". Philadelphia Daily News. Philadelphia: Interstate General Media. Retrieved April 21, 2012. [dead link]

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn honored as Columbus airport is renamed for him". The Columbus Dispatch. Columbus, Ohio: New Media Investment Group.

- Jump up ^ Berlinger, John Newsome; Berlinger, Joshua. "John Glenn—astronaut, ex-senator—gets successful heart surgery". CNN. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner).

- Jump up ^ Strickland, Ashley (December 7, 2016). "Former senator, astronaut John Glenn hospitalized". CNN.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn, in declining health, is hospitalized". Cleveland Plain Dealer. December 7, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Former senator, astronaut John Glenn in OSU hospital". Cincinnati Inquirer. December 7, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Former astronaut John Glenn hospitalized in Columbus". Columbus Dispatch. December 8, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "John Glenn, American hero, aviation icon and former U.S. senator, dies at 95". The Columbus Dispatch. Columbus, Ohio: New Media Investment Group. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn, First American to Orbit the Earth, Dies". ABC News. United States: ABC. December 8, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "Statement by the President on the Passing of John Glenn", The White House, Dec. 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ "Hillary Clinton Marks Passing of John Glenn"

- Jump up ^ "President-elect Donald Trump honors the late John Glenn", Fox25, Dec. 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff, Macmillan (1979)

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn dies: Trailblazing US astronaut was 95", BBC, Dec. 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn, First US Astronaut to Orbit the Earth, Dies at 95", Voice of America, Dec. 8, 2016

- Jump up ^ "Hokulea’s Nainoa Thompson receives National Geographic award", KHON TV, June 18, 2016

- Jump up ^ Porter, Lorie. John Glenn's New Concord, Arcadia Publ. (2001) ebook

- Jump up ^ [1][dead link] Archived May 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- Jump up ^ Navy christens USNS John Glenn, Pueblo Chieftain, February 1, 2014, retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Jump up ^ "National Aviation Hall of fame: Our Enshrinees". National Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- Jump up ^ "John Glenn | Astronaut Scholarship Foundation". Astronautscholarship.org. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ "National Winners | public service awards". Jefferson Awards.org. Retrieved August 30, 2013.

- Jump up ^ "Recipients of the Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service", wilsoncenter.org; retrieved November 18, 2011.

- Jump up ^ "Honorary Degrees | Office of the President". President.williams.edu. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ Linkhorn, Tyrel (May 24, 2010). "Honorary doctorate degree for John Glenn". The Lima News. Lima, Ohio: Ohio Community Media. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- Jump up ^ "51 Heroes of Aviation". Flyingmag.com. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- Jump up ^ Victor, Daniel (September 12, 2016). "Meet New Glenn, the Blue Origin Rocket That May Someday Take You to Space". The New York Times. New York City: The New York Times Company. Retrieved September 13, 2016.

Further reading

- Glenn, John H.; Taylor, Nick (2000). John Glenn: A Memoir. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-58157-0.

- Fenno, Richard F., Jr. The Presidential Odyssey of John Glenn. CQ Press, 1990. 302 pp.

- Mersky, Peter B. (1983). U.S. Marine Corps Aviation — 1912 to the present. Annapolis, Maryland: The Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America. ISBN 0-933852-39-8.

- Shettle Jr., M. L. (2001). United States Marine Corps Air Stations of World War II. Bowersville, Georgia: Schaertel Publishing Co. ISBN 0-9643388-2-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Glenn. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Glenn |

- United States Congress. "John Glenn (id: G000236)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "COLONEL JOHN H. GLENN, JR., USMC(RETIRED)". Who's Who in Marine Corps History. Retrieved December 18, 2006. [dead link]

- John Glenn: A Journey, nasa.gov

- John Glenn Honored as an Ambassador of Exploration, nasa.gov

- John & Annie Glenn Historic Site and Home

- John Glenn profile[dead link], glennschool.osu.edu

- John Glenn's Flight on Friendship 7, MA-6 – as heard on KCBS Radio at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- John Glenn's Flight on Friendship 7, MA-6 – complete 5-hour capsule audio recording

- John Glenn's Flight on the Space Shuttle, STS-95

- Iven C. Kincheloe Award winners

- John Glenn IMDb profile

- John Glenn profile, National Aviation Hall of Fame website

- Glenn profile at Encyclopedia of Science, daviddarling.info

- Glenn profile, International Space Hall of Fame website

- Biodata, Astronautix.com

- John Glenn archive[dead link], osu.edu

- John Glenn: Unpublished Photos — slideshow[dead link], Life Magazine website

- John Glenn: A Life of Service, pbs.org

- Obituary: John Glenn bbc.co.uk

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Gilligan |

Democratic nominee for Senator from Ohio (Class 3) 1974, 1980, 1986, 1992 |

Succeeded by Mary Boyle |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by Howard Metzenbaum |

United States Senator (Class 3) from Ohio 1974–1999 Served alongside: Robert Taft, Howard Metzenbaum, Mike DeWine |

Succeeded by George Voinovich |

| Preceded by William Roth |

Chairperson of Senate Governmental Affairs Committee 1987–1995 |

Succeeded by William Roth |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Edward Brooke |

Oldest living United States Senator 2015–2016 |

Succeeded by Ernest Hollings |